Published on

Provoked vs. Unprovoked Clots: What’s the Difference?

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a blood clot that forms in a vein. Clots most commonly form in the legs, but pieces of the clot can break off and move to the lungs, causing a pulmonary embolism (PE). PE is fatal in up to 30% of cases. For a person with a blood clot in a vein, once the initial clot has dissolved, it’s important to reduce the risk of a future clot.

Doctors generally classify a venous blood clot as either “provoked” or “unprovoked.” This distinction can have major implications for long-term treatment. So, what does it mean for a blood clot to be provoked or unprovoked? Is one type more dangerous than the other? How might this distinction affect your treatment plan?

CAUSES OF PROVOKED BLOOD CLOTS

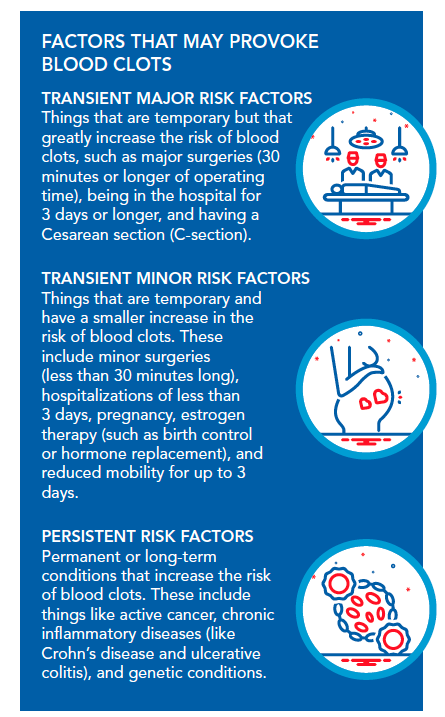

A blood clot is considered to be provoked when there’s a clear trigger for the clot, while an unprovoked clot happens without an obvious cause. (See figure below.)

If you experience a blood clot and have an obvious risk factor, then your clot is considered provoked. Doctors will likely be able to pinpoint why the clot happened.

An unprovoked clot doesn’t have a clear cause. In fact, unprovoked clots are sometimes called “idiopathic blood clots,” meaning that doctors don’t know why the clot occurred.

The distinction between a provoked and an unprovoked clot is not always black-and-white. For example, if you have a clot several months after a major surgery, it may not be obvious whether the surgery led to the clot or not. Current treatment guidelines specify that a clot is considered to be provoked if it occurs within three months after a major transient risk factor, or two months after a minor one.

TREATMENT IMPLICATIONS

After any blood clot, whether it’s provoked or unprovoked, blood thinners (anticoagulants) are generally prescribed for a minimum of three months. If blood thinners are stopped sooner, there’s a risk that the clot will form again in the same place where it first occurred.

After three months, the treatment plan can vary. Some patients stop taking blood thinners, while others continue to take them over the long term. This decision is based on the risk of the patient having another clot versus the risk of bleeding caused by being on a blood thinner.

In general, an unprovoked clot is considered to be riskier than a provoked clot. Since unprovoked clots occur without any known precipitating factors, they could indicate an underlying tendency to form clots. Research has shown that patients with unprovoked clots have a high risk of having another clot in the future. Because of this, these patients are likely to be prescribed blood thinners for the long term to reduce their risk.

While unprovoked clots are considered to be riskier in general, clots that are provoked by a persistent (or long-term) risk factor are the riskiest of all, resulting in a very high risk of having another clot. For example, a patient with cancer who experiences a clot would usually be given long-term blood thinners, at least until their cancer goes into remission.

By contrast, a provoked clot that’s caused by a transient risk factor is less likely to be a long-term concern. For example, if a patient has a knee replacement and experiences a clot, the major surgery is a clear trigger. Once they’ve recovered from the surgery, their chances of a clot go down dramatically. This patient would likely be given blood thinners for three months after the clot, but not after that.

PERSONALIZING CARE

Beyond general treatment guidelines, there are some individual factors that can influence whether or not a particular patient gets long-term blood thinners. Even for a patient with a provoked clot, long-term blood thinners may still be preferred in some cases.

Although certain risk factors classify a clot as “provoked,” other contributors – such as a strong family history of blood clots, obesity, or certain chronic diseases (like kidney disease) – may increase the risk of a future blood clot. Having one or more of these factors may tip the balance towards taking long-term blood thinners, even in a patient with a provoked clot.

Imagine that you had a clot provoked by a major surgery. This is a transient risk factor, which would normally warrant taking blood thinners for only three months. However, if you were overweight or had other risk factors, for example, it might be worthwhile for you to take blood thinners for longer than three months to reduce the risk of future clots.

The location of a clot is also important. Blood clots in the lower legs are more common and less concerning than clots in other parts of the body. Studies have shown that people with a single unprovoked clot in the lower leg may not need long-term blood thinners, while those with a clot in another area (such as the thigh or arm) should be given blood thinners for a longer duration.

Another consideration is the risk of a fall. If a patient has a higher-than-average risk of falls, then they may be at increased risk of bleeding from taking blood thinners. This bleeding risk may be greater than the risk of another clot, so they may not be put on long-term blood thinners.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution for taking blood thinners after a clot. Instead, doctors will carefully weigh each patient’s risk factors for a future blood clot and determine whether the increased risk of bleeding caused by blood thinners would be outweighed by the decreased risk of another clot.

If you’ve experienced a blood clot, then your medical team will evaluate you to determine your risk of future clots. They might recommend that you take blood thinners for a few months, or they may advise you to take them for longer. This decision is highly individualized. If you have any questions about why particular recommendations were made in your case, don’t hesitate to ask your medical team to explain this to you.

References

American Society of Hematology: Duration of anticoagulant therapy for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

AHA Journals: A Patient’s Guide to Recovery After Deep Vein Thrombosis or Pulmonary Embolism

National Library of Medicine: Treatment of distal deep vein thrombosis

Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: Categorization of patients as having provoked or unprovokedvenous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of ISTH

National Library of Medicine: Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Venous Thrombosis

*Originally published in The Beat — October 2022. Read the full newsletter here.