Last updated on

Chronic Blood Clots…In Your Lungs? Understanding CTEPH

When a blood clot occurs, your body may naturally dissolve it through an internal “clot-busting” process. At the same time, anticoagulant medications (blood thinners) can keep a clot from growing larger and can also prevent new clots from forming. But in a small number of patients who’ve had blood clots in their lungs—a pulmonary embolism (PE)—the clots don’t go away, resulting in a condition called chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

WHAT IS CTEPH?

“To really grasp CTEPH, patients need to understand the concepts put forth by the term itself, so 1) chronic thromboembolism and 2) pulmonary hypertension,” says Dr. Bill Auger, a pulmonologist and CTEPH specialist at the Temple University Lewis Katz School of Medicine.

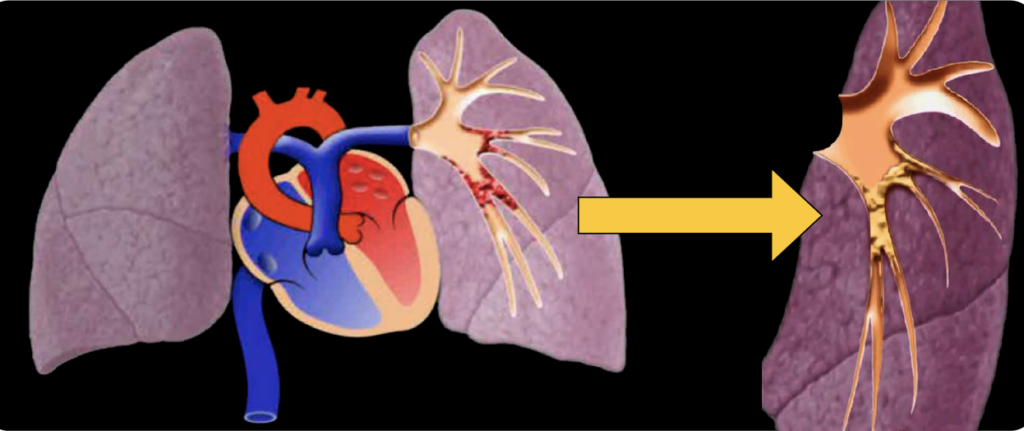

So, how does a “fresh” or new blood clot turn into a “chronic” blood clot? “In some individuals who have a PE, the clot sticks to the wall of the pulmonary arteries and forms scar-like material within the artery over time. This material can narrow or block the artery. If it’s there long enough, you can then develop pulmonary hypertension (PH). In other words, these clots are the chronic thromboemboli that lead to PH in CTEPH,” Dr. Auger explains.

PH is high blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs. After your blood carries oxygen to the tissues in your body, it returns to the right side of the heart. The right heart then pumps blood into your lungs to get oxygenated again. The pressure that the right heart pumps against is called the pulmonary pressure, and PH occurs when this pressure is too high. If PH is left unattended, the right heart has to work much harder to pump blood to the lungs. This increased workload on the heart can cause shortness of breath and make it difficult to walk, climb stairs, do housework, etc.

Importantly, there are several medical conditions that can increase pulmonary pressure, so a person can have PH that’s completely unrelated to a blood clot. However, a blood clot in the lungs—a PE—is always the source of CTEPH. CTEPH can develop when many small clots form over time, so it’s possible for patients to develop the condition without knowing that they’ve had a PE before. In fact, CTEPH registries around the world have shown that 25-30% of patients with known CTEPH don’t have a history of PE documented in their patient chart. CTEPH can also affect individuals at any age.

HOW COMMON IS CTEPH?

An estimated 3% of PE patients develop CTEPH, but it’s hard to know exactly how many people are affected because CTEPH is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. “It doesn’t have clear-cut symptoms. The big signal is that shortness of breath when a person tries to do something – but that’s a nonspecific symptom that occurs with many medical issues,” Dr. Auger says. “If you’re having shortness of breath and you and your doctor know that you’ve had a PE, it’s a little easier to connect the dots and get to CTEPH. But if you have trouble breathing on exertion for no obvious reason, your healthcare provider should start thinking about pulmonary vascular disease as a possible cause.”

DIAGNOSIS

If CTEPH is suspected, your doctor will likely obtain an echocardiogram (echo) to get a sense of what the heart is doing and a ventilation/perfusion (VQ) scan, which is a nuclear medicine study to measure breathing and circulation in the lungs.

Dr. Auger points out that these tests are not diagnostic for CTEPH on their own, but they’ll bring a clinician down the appropriate path. “If you have an echo and VQ scan that are both abnormal, you’re on the right street for diagnosing CTEPH. You just need additional studies to get to the right house.”

Additional testing typically includes a CT scan to detect blood clots, and a pulmonary angiogram, which is a test that uses injectable dye to highlight blockages in the arteries of the lungs. A procedure called a right heart catheterization is also typically performed to accurately measure the extent of PH and right heart strain. It’s appropriate for your doctor to refer you to an expert PH or CTEPH center to assist with diagnosis and treatment.

TREATMENT

Unlike many types of PH, CTEPH is potentially curable. “The key thing I want patients to know is that we can cure CTEPH with surgery, and that’s exciting,” exclaims Dr. Auger. “The procedure is called a pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. When the surgeon gets into the pulmonary artery, they carefully peel off the clot material that’s adherent to the artery wall. Afterwards, patients are able to breathe again. It’s remarkable. Quality of life improves dramatically – but the surgery is only able to cure PH and its symptoms. A person’s diabetes, COPD, etc. won’t go away with this surgery and patients will still have to manage those.”

In addition, some patients aren’t surgical candidates. “Sometimes, a surgeon will say to me, ‘I can’t get that clot out, it’s inoperable,’ and then I know I have to move forward with other options,” Dr. Auger explains. “Whether or not CTEPH is operable is strictly a technical consideration determined by the surgeon; however, patients may have other medical or logistic issues that prevent them from having surgery, or they may not want surgery. The good news is that there are options we can offer patients now that we didn’t have 10 years ago, including balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) and PH medications.”

BPA is a procedure that uses balloons to open narrowed or blocked blood vessels and restore blood flow to the lungs. Although the procedure doesn’t remove clots, it helps relieve PH, reduce shortness of breath, and improve exercise capacity. Typically, patients need more than one BPA procedure, but they often experience a difference in symptoms afterwards. “They aren’t cured, but they feel better. They can walk upstairs again, they can go for walks in their neighborhood, etc. Every patient will be different, and their outcome goals will be different. The results will also depend on their age and comorbidities,” says Auger.

Medication is another treatment option. Riociguat is an FDA-approved oral agent for CTEPH patients who can’t have surgery or who still have symptoms after a procedure. This medication is often prescribed in combination with BPA, but some patients use it as standalone therapy.

All CTEPH patients need to be on lifelong anticoagulation (blood thinners) as well, even if they’ve been cured with surgery. The goal is to prevent new clots from forming. Patients have typically received warfarin, but some centers are beginning to move towards direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to maximize patient convenience.

COST/INSURANCE CONSIDERATIONS

Insurance coverage will vary from plan to plan, but many insurers, including Medicare, are familiar with CTEPH and either partially or fully cover CTEPH related services. CTEPH centers throughout the US have staff in place to help patients navigate insurance-related issues.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- CTEPH is underrecognized, even though it’s curable in many patients. It’s important to get a diagnosis so you can be treated appropriately.

- Talk to your healthcare provider as soon as possible if you have shortness of breath or fatigue that doesn’t resolve, especially if you have a history of blood clots. Anticoagulation alone will not prevent the progression of CTEPH!

- There are several excellent CTEPH centers throughout the US. Patients should use these centers as a resource. The Pulmonary Hypertension Association has a list of comprehensive PH care centers on their website. www.CTEPH.com is another good patient website.

- CTEPH treatment and management have changed dramatically over the past few years. There are many options now that weren’t available even a decade ago!