Last updated on

Clinical Trials 101: Your Guide to the Gold Standard of Research

What exactly happens in a clinical trial? We asked Dr. Suresh Vedantham, Assistant Dean for Clinical Research and Professor of Radiology and Surgery at Washington University School of Medicine, for answers to common questions about trial research.

Q: What does a clinical trial involve?

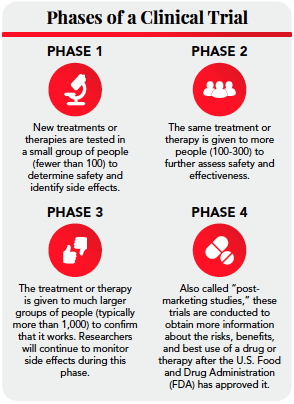

A clinical trial is a study that’s designed to answer a question about a diagnostic method, a treatment, a vaccine, or about health care in general. Clinical trials are typically done in four phases. (See infographic)

All trials are designed according to what’s called a protocol, which is basically the plan for doing the study, and that plan must be approved by an independent body called an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB, which includes healthcare providers and laypersons, reviews the ethics and safety of the trial from the perspective of a patient who might be in that study.

Once the IRB approves the trial, researchers start recruiting patients for the study. Common marketing techniques for clinical trials include social media, radio, TV, billboards, or signs/posters in hospitals. Researchers will also partner with providers. So, if I’m trying to enroll people with a certain condition, I’ll reach out to doctors who see patients with that condition, I’ll ask if I can put up ads in their clinics, and my team and I will educate the doctors and staff so they can pass along the information to their patients. We’re also able to use electronic medical records to find participants for some studies – as long as adequate privacy protections are in place.

There are unique ways to find participants if you’re studying an in hospital population, too. For example, if you’re looking at a condition that requires a CT scan for diagnosis, we may be able to obtain information about that CT scan and identify the patient that way, and then we can approach the patient in person.

Importantly, all recruitment methods need to be approved by the IRB.

Q: What are the benefits of participating in a trial?

As a trial participant, you’ll generally be part of a structured program and closely monitored. For some types of trials, you may have access to treatments that you wouldn’t have otherwise; for example, investigational treatments that aren’t FDA approved yet. And, of course, you’ll get the satisfaction of knowing that what you’re doing will ultimately benefit other people. I’ve also found that patients really like the concept of being actively involved in their own care. Oftentimes, trials enable you to ask more questions and learn a bit more about your condition.

That said, it’s important to know that you won’t get worse or inferior care if you don’t participate in a trial. There are some inconveniences that come with trial participation as well. Typically, you’ll have to devote some time to traveling to and from study visits, and patients do take on some risk when they join a trial since the risks and benefits of some treatments/therapies aren’t fully understood yet.

Q: What’s the next step once I agree to participate in a trial?

A member of the research team will ask for your informed consent, which involves a discussion between you and the researcher or team member to review the study protocol, discuss what your participation would entail, and address the potential risks and benefits of participating in the trial. You’ll also receive a written description that summarizes the goals of the study and what you’ll be expected to do. Most trials include study visits, and the consent document will outline what will occur at these visits.

Local travel expenses and participant time (for example, coming for a study visit, parking, etc.) are typically covered as part of the study. Compensation is spelled out in the consent document upfront, along with how long the study will go on for.

Before giving your consent, you should feel free to ask any questions that come to mind so that you understand every component of the trial process. It’s completely your choice to take part in the study. If you decide to provide informed consent, you’ll be asked to sign a consent document, either in person or online.

After giving consent, you may be asked to participate in some baseline studies. These assessments can include a medical history, physical exam, imaging studies, blood draws, or just written questionnaires.

You can withdraw from the study at any time.

Q: What should I expect once the study starts?

Although every trial requires different levels of participation, you’ll likely have regular contact with a member of the research team. We typically call that person a coordinator; they’ll facilitate and guide you through your study visits.

During the study, there will be some type of routine assessment to determine what’s happening now that we’ve changed a component of your care. So again, we may use blood tests, imaging studies, questionnaires, etc. to look at what’s working or not working, or to monitor changes.

You’ll be notified when the study is over and thanked for your participation. Once the study outcomes are known, you may also receive a letter detailing the results.

Q: Are clinical trials safe?

Some treatments being studied turn out to be more effective or safer than existing treatments, and and some don’t. You only know that once the trial is over – but the IRB would not allow a trial protocol to proceed if there were obvious red flags upfront. In addition, the study plan needs to incorporate safeguards for patient safety, appropriate to the type of study being done.

For treatments that might carry some risk, an independent expert board called a Data and Safety Monitoring Committee will periodically review the ongoing results of the trial. This committee doesn’t have any relationship to the researchers, so they don’t have a stake in the trial continuing or not; they just want to ensure safety. If one treatment turns out to be conclusively better than another in the middle of the trial, the board would stop the study. Likewise, the trial would be suspended if one treatment clearly causes harm.

Q: How is patient data kept private?

The specifics around patient privacy must be provided upfront to the IRB, and they won’t approve a trial protocol unless they’re confident that adequate safeguards are in place. Beyond that, researchers generally store health information in a secure study database where participants are assigned an anonymous ID number.

Privacy is also outlined in the informed consent document that patients sign. There will be statements about what the research team would like to do with the information; in other words, who would have access to it down the road. Researchers often want the ability to share information with other researchers so we can obtain the most good from it, as long as privacy protections are appropriately maintained. You should always make sure that you understand the privacy statements in the informed consent document prior to signing it.

We can never say in the modern world that anything is 100% hackproof, but there are very strong efforts to prevent data breaches in research. Researchers think about privacy explicitly when designing protocols.

Q: Will my treatment outcome change if I participate in a trial?

A trial plan will always detail what parts of treatment you’d normally get and what new treatments you might get in the trial. If there are any standard treatments you’d have to give up in the trial, that should be made clear, too. It’s not easy to predict outcomes upfront because the change in care is often what’s being studied in the first place.

Q: How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected clinical trial research?

Outside of vaccine trials, COVID-19 has had a significant impact on study participation. Most researchers have been trying to find ways to make it easier for patients to participate in studies with a minimum of in-person visits to the study center. We’re leveraging technology as much as we can so that patients can fill out questionnaires and sign informed consent documents from the comfort of their home. For visits that must be done in person, we’re being proactive to help patients safely navigate research visits. We’re ensuring that they have safe spaces for waiting, that they’re distanced from other people, that they’re wearing masks, and that everyone is doing their part to maintain a safe environment. The trial I’m currently working on, called C-TRACT, now allows some visits to be done remotely when needed and I think patients appreciate that. (For more information on C-TRACT, see below.)

*Originally published in The Beat – October 2020. Read the full newsletter here.