Last updated on

Bleeding and Blood Thinners: What to Know About Heavy Periods

When choosing an anticoagulant (blood thinner) for a patient, prescribers must weigh the risk of a major bleed against the risk of a blood clot. A major bleed is a medical emergency, but doctors are less concerned about minor bleeds, such as nosebleeds, easy bruising, etc, which don’t require urgent medical care.

However, bleeding that’s considered “minor” can greatly impact a person’s quality of life. Minor bleeding can cause significant anxiety and result in missed work, school, or social obligations and activities. About 54% of patients on anticoagulants report that they’ve adjusted their lifestyles as a result of bleeding.

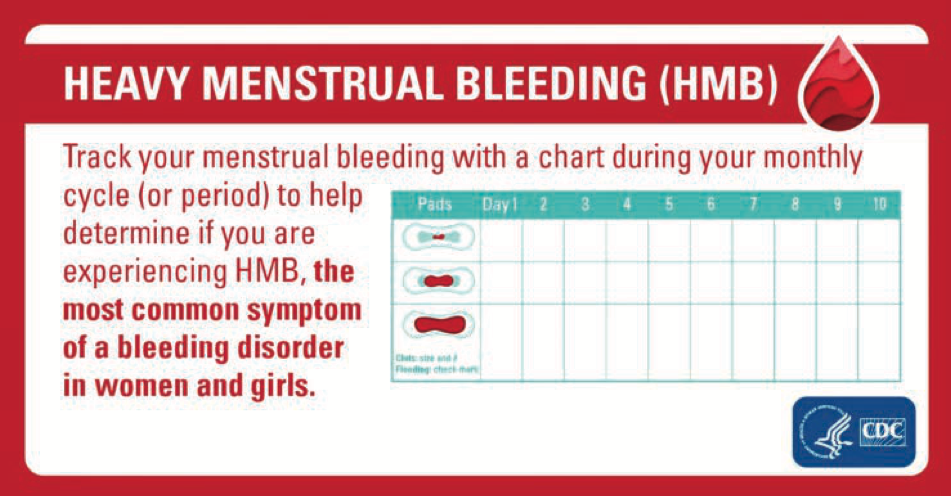

With the range of effects that bleeding can have, many experts now prefer the term “patient-relevant bleeding” instead of “minor bleeding.” Even though such bleeding may not be life-threatening, it can still greatly impact a person’s life. In women who take blood thinners, heavy periods—also called heavy menstrual bleeding or HMB—is a common example of patient-relevant bleeding.

How does anticoagulation affect a woman’s period?

Women on anticoagulation may have periods that are significantly heavier than before they started treatment. Studies have shown that up to 70% of women on oral blood thinners experience menstrual bleeding that’s heavy enough to be of concern. Some women may also experience other types of abnormal bleeding, such as bleeding between periods or after menopause.

HMB can significantly disrupt a woman’s life. Women with heavy bleeding may have to change their pad, tampon, or cup very frequently (sometimes as often as every half-hour) and can experience leakage if their bleeding is too heavy for menstrual products to absorb. If left untreated, HMB can also lead to a low red blood cell count, better known as anemia.

How can HMB be managed?

Most women who take blood thinners should continue their treatment unless told otherwise by their doctor. (Never stop taking anticoagulation—or any medication—without consulting your doctor or prescriber.) Some women have noticed improvement in HMB after switching to a different anticoagulant. If you have HMB, your doctor may be able to prescribe a different blood thinner.

After a discussion with your doctor, hormone treatments are often the first option for managing HMB. These therapies can make the uterine lining thinner, resulting in less menstrual bleeding. They include:

- A combined hormonal contraceptive (known as a CHC or birth control pill, patch, or ring): CHCs contain both estrogen and progesterone, which can help improve HMB. While there is an increased risk of blood clots with these medications, data shows that for many women, the benefits of birth control pills for regulating HMB outweigh the risk of clots while taking blood thinners.

- Progestin-only hormone therapies: These include a progestin-only pill taken daily, an implant placed under the skin, a long-acting injection, or a progestin-containing intrauterine device (IUD).

Beyond hormone therapy, there are some procedures that can resolve HMB – but these are reserved for extreme cases of HMB*. These procedures include:

- Endometrial ablation: In this procedure, an instrument is inserted through the cervix that uses heat or cold to ablate (remove) the endometrium (the lining of the uterus).

- Uterine artery embolization: A procedure that blocks blood supply to the uterus to help control bleeding.

- Hysterectomy: A surgery to completely remove the uterus. This procedure is permanent and cannot be reversed, so it is truly a last resort.

*It is critical to know that while these procedures can improve or resolve HMB, they also threaten a woman’s fertility or ability to have a healthy pregnancy. These treatments are only recommended for women who are done having children or who are certain that they do not want children.

If you take an anticoagulant and experience any type of bleeding that concerns you (including bruising easily, bleeding from cuts, having nosebleeds, or bleeding into the whites of your eyes), talk with your doctor about it. However, you should never stop your anticoagulation on your own, because this could increase your risk of a serious clotting event.

You should also discuss your HMB with your doctor.

Though it can feel awkward or embarrassing to talk about your period, your doctor has expertise in navigating these conversations. Additionally, your healthcare team can’t give you the best care if they don’t know what you’re going through.

Helpful information to share includes:

- How many days apart your periods are

- How long each period lasts

- How many pads/tampons you go through on the heaviest day of your period

- Whether you experience bleeding or spotting between periods

- What changes have occurred since you started taking anticoagulants

Tracking your menstrual cycle or keeping a diary can also help you document this information for your doctor.

You may also want to spend some time learning more about HMB so you can prepare any questions that you’d like to ask during the appointment. There are a variety of excellent patient resources available on this topic.

*Originally published in The Beat — August 2023. Read the full newsletter here.